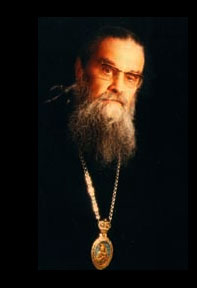

A Brief Biography of Archbishop Anthony

(Bartoshevich, +1993)

of Geneva and Western Europe

Bernard le Caro

Archbishop Anthony was born Andrei Georgievich Bartoshevich in St Petersburg, Russia, in 1910. His parents, Yuri (George) Vladimirovich Bartoshevich, was a military engineer, a colonel of the Imperial Army, and Ksenia, nee Tumkovskaya, were both pious people. At the beginning of the Revolution, Andrei left for Kiev with his mother to his grandmother’s home, while his father joined the Volunteer Army. During the NEP [New Economic Policy], they were able to flee to Germany, then to Belgrade to reunite with his father, who worked there as an engineer. Andrei finished the Russian-Serbian Gymnasium and in 1931 began a three-year course of studies at Belgrade University’s Technical School. Archbishop Anthony was born Andrei Georgievich Bartoshevich in St Petersburg, Russia, in 1910. His parents, Yuri (George) Vladimirovich Bartoshevich, was a military engineer, a colonel of the Imperial Army, and Ksenia, nee Tumkovskaya, were both pious people. At the beginning of the Revolution, Andrei left for Kiev with his mother to his grandmother’s home, while his father joined the Volunteer Army. During the NEP [New Economic Policy], they were able to flee to Germany, then to Belgrade to reunite with his father, who worked there as an engineer. Andrei finished the Russian-Serbian Gymnasium and in 1931 began a three-year course of studies at Belgrade University’s Technical School.

He then decided to devote his life to serving the Church, and, before completing his technical studies, enrolled in the Theological Department. Among his professors was the great theologian and podvizhnik of the Serbian Church, Fr. Justin (Popovich, +1979), who left an impression on the future bishop, and also Sergei Troitsky (+1972), whose strictness with regard to canon law also left a mark on the future pastor (1). Andrei maintained correspondence with Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky, +1934), and with the monks of Milkovo Monastery, which was turned over to Russian monks in 1926, led by Archimandrite Amvrosy (Kurganov, +1933), a highly-spiritual person. “The new abbot,” we read in the monastery chronicles, “drew people to Milkovo like a magnet, the best monks of the Russian emigration.” (2)

At the time, Andrei became interested in icon-painting, and studied under the great iconographer Pimen Sofronov. He painted several icons, including “All Russian Saints” for Holy Trinity Church in Belgrade, and “Descent Into Hell,” for the Iveron Chapel crypt in Belgrade, where Metropolitan Anthony was buried. In 1941, Andrei was tonsured into the lesser schema at Tuman Monastery, where Milkovo’s monks had moved, and given the name Anthony (in memory of St Anthony of the Kiev Caves). Fr Anthony was then ordained a hierodeacon, then hieromonk, by Metropolitan Anastassy (Gribanovsky, +1965) in Holy Trinity Church in Belgrade, where he stayed to serve. In February 1942, Fr Anthony was appointed teacher of Law of God at the Russian Cadet Corps in Bela Tsrkva, not far from Belgrade, where he taught the cadets icon-painting. Fr Anthony had a special approach towards dealing with youth; in his pastoral, and later archpastoral, ministry, he would draw them closer to regular church life.

In the words of a former cadet, “Hieromonk Anthony Bartoshevich, while still very young, knew us cadets well, both senior and junior, and was a morale-booster for us, and sometimes tutored us in our written Latin studies.” (3)

In 1945, after World War II, the Russian community in Belgrade joined the Moscow Patriarchate. According to the rector of the Belgrade church, being “a good monk and a gifted individual,” (4), Fr Anthony, by ukase of Patriarch Alexy I, was elevated to the rank of archimandrite. As did many emigres, Fr Anthony thought that the hour of emancipation for the Church in Russia had arrived. Therefore, he wished with all his heart to serve the Church in the Homeland, but Divine Providence deemed otherwise. The rector of the Belgrade church wrote to Patriarch Alexy: “Being alone, without any means of support, Fr Anthony has patiently awaited for the fourth year now an appointment somewhere. Having received no response to his requests, he is falling to despair and thinks that his hopes to return to his homeland will never be fulfilled…” (5). It is very likely that the return of the young archimandrite to the USSR did not suit Karpov, and a response never came.

Not wishing to simply fulfill his own desires, Fr Anthony did not persist, and left Yugoslavia. It was difficult for him to leave the country that became his second homeland, yet in the face of everything, he considered himself fortunate: “I am like a babe in his mother’s arms,” that is, he always obeyed God’s will. In his words, “one must accept the will of God without grumbling, believing that the Father, loving us, gives us what we need and that which is beneficial to us, and that He is preparing for us such joyous communion with Him that we on earth cannot even imagine it.” (6) So in 1949, he moved to Switzerland, where his brother lived, Bishop Leonty of Geneva of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, who was known for his holiness.

From 1949 on, Fr Anthony served in different churches of the Western European Diocese of ROCOR, including Lyon, where he painted the iconostasis and an icon of the ancient St Irineus of Lyon for the local church. From 1952 until 1957, he lived in Brussels. A great many emigres from the Soviet Union arrived in Belgium, whose material and emotional condition was grave. Fr Anthony traveled throughout Belgium to visit the suffering. As always, Fr Anthony paid special care to the youth, and actively participated in the establishment of the first Russian Orthodox school in Brussels. He organized summer camps where over a hundred young people would gather. Since many parents could not afford to send their children, Fr Anthony himself collected funds for them. Thanks to his efforts, a local branch of the Vityazi scouts was opened.

In 1957, after the unexpected death of Bishop Leonty the previous year, Fr Anthony was consecrated Bishop of Geneva by a group of hierarchs headed by the Archbishop of Western Europe of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, St John (Maximovich, +1966).

As a bishop, Vladyka traveled extensively throughout his diocese, often visiting his beloved Lesna Convent, piously performing divine services, ministering to the faithful and offering spiritual support. When Vladyka would visit his parishes, he would read the Six Psalms and the matins canons during all-night vigil, at the end of which he would bless every single worshiper, and then would stay for a discussion with the people. The following morning, Vladyka would celebrate Divine Liturgy. Vladyka’service was deeply prayerful, simple and yet grandiose. The words of Archimandrite Kyprian (Kern) about Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) can be applied to his student, Vladyka Anthony of Geneva: “Complete confidence in the church Typicon and rites. He possessed wonderful rhythm and a dispassionate bearing in the way he conducted divine service, and in his reading, in his liturgical exclamations, he added nothing of his own. He read intelligently, clearly, dispassionately.” (7) During the evening, Vladyka would gather young people together for discussions, during which he talked about the Holy Gospel. The youth really loved Vladyka, and, as they say, followed him in droves. Vladyka wrote a wonderful article on youth ministry called “Our Successors.”

Despite the many responsibilities he had before his diocese, Vladyka lived a monastic life as before. In Geneva, he began to gradually return divine services to a stricter adherence to the Typicon. Even when there were no services, he would read the entire cycles of services at his residence. When people would ask him how it was that he was perpetually happy, he would respond that this can be achieved through intense morning prayer. Vladyka observed lenten periods strictly, following the Typicon closely. While traveling during a lenten day, even if he ate at a restaurant, he ate only lenten food, saying that the Typicon simply does not make dispensations for travelers. Yet even while he was strict with himself, he was understanding with others.

For years, Vladyka led pilgrimages to the Holy Land, which for him, according to Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesensky, +1985), was “the fifth Gospel.” At each holy site, Vladyka Anthony would read the corresponding Gospel passage to the pilgrims. One such pilgrim wrote that after the rite of blessing the waters on the Jordan River, everyone would immerse themselves as Vladyka would speak these powerful words: “Let no one be troubled that the water appears unclean. For the Holy Spirit descended upon these waters, which has defeated all matter. This water has acquired the power to heal, a source of life and health. Draw from it, drink it to the salvation of your souls and your bodies!” (8). Vladyka would also organize pilgrimages to the holy sites of the West, for instance, to the city of Lyon, the place of the martyrdom of Saints Blandine, Alexander and Epipode (177 AD), for, much the same as his predecessor, St John (Maximovich), he revered the ancient Orthodox Christian saints of the West. That is why he instructed Fr Peter Cantacuzene (the future Bishop Ambroise of Vevey), to compose a service “To All the Helvetic Saints.”

Vladyka Anthony himself edited and published the Vestnik Zapadno-Evropeiskoi Eparkhii Russkoi Tserkvi za Rubezhom [“The Messenger of the Western European Diocese of the Russian Church Abroad”], for which he wrote theological articles, including “On Life of the Soul Beyond the Grave” (9), which was later published in brochure form. In 1969, he drafted a remarkable address in which he stressed the unity of the Church of Christ: “If there is One Head, there is one Body! We are all one in Christ and His Church (Corinthians 3:11). Therefore, there could not be two, three or many Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Churches… for did Christ divide Himself? (1 Corinthians 1:13), asked Apostle Paul sorrowfully of his contemporary Christians. Has His Church then been divided, we ask today?” (11). Despite the fact that he was a strict Orthodox Christian, Vladyka never took an extreme position. At the All-Diaspora Council of 1974, Vladyka spoke forcefully in favor of ecclesiastical unity and against the self-isolation of ROCOR, and in his report, outlined the “duty of ROCOR before the Church and the Homeland" thusly (12):

1) “To preserve the purity of Orthodoxy, rejecting any temptations of atheism and modernism. In other words, courageously follow the path inscribed on the tablets of law of our Church.

2) To be the bold and free voice of the Church of Christ, speak the truth without compromise, which our First Hierarchs have thus far done.

3) Using our freedom, to be understanding of those enslaved, taking care not to condemn anyone carelessly, but to understand, support, and show brotherly love.

4) To cherish and preserve ecclesiastical unity, sensing that we are part of the living universal Church of Christ and worthy to bear the banner of the Russian Church within Her.

5) To avoid self-isolation, for the spirit of the Church is unifying, not divisive. Let us not seek heretics where ever they may be, and let us fear exaggeration in this area.

6) To call all Russian Orthodox Christians and their pastors who have left us towards unity. Let us call them not through sanctions, but with brotherly love in the name of the suffering Russian Church and our much-suffering Homeland.

7) Let us turn to face the renascent Russia, extend a helping hand to the best of our abilities!”

He ended his speech with the following words: “What is more important for us, the Church itself and the living forces within Her, or Her temporary, maybe unworthy representatives? Shall we on their account tear ourselves away from Universal Orthodoxy, in which most think like we do, in which, despite our unworthiness, the Holy Spirit breathes? Whom then would we be punishing? Only ourselves!" (13). Learning of Vladyka Anthony’s words, the great Athonite, Elder Paisios (Eznepidis, +1994), told a pilgrim from Paris once “Your Anthony is a hero! He is not with them [the ecumenists] and not with the others [the unreasonable zealots]!” In fact, Vladyka acted humbly, doing nothing without seeking advice, and on church matters often consulted Archbishop Nathaniel (Lvov, +1985), Protopriest Igor Trojanoff (+1987) and Abbess Theodora (+1976) and Abbess Magdalena (+1987) of Lesna Convent. He would always ask one pilgrim who made frequent trips to Mt Athos what the Fathers of the Holy Mountain thought about a particular ecclesiastical question.

Vladyka was a fervent proponent of ecclesiastical peace in the diaspora. In the 1960’s, there was hope that the Parisian Exarchate would soon unite with ROCOR. Alien to any form of careerism, Vladyka dared not accept the rank of archbishop offered by the Synod of Bishops, since the Parisian Exarchate was already headed by one. Only when any chance of unification faded away did Vladyka accept the position, but continued to harbor love for the clergymen and laity of the Exarchate. As far as the Moscow Patriarchate was concerned, Vladyka avoided extreme positions, witnessed by his letter to Fr Dimitri Dudko: “The late Archbishop John, whom we all respected and loved, would say ‘the official Church in Russia, of course, possesses grace, though one bishop or another might conduct themselves poorly.’” (14). In 1985, he visited Belgrade and prayed at Liturgy in the Russian church of the Moscow Patriarchate.

One of the great events in the life of Vladyka Anthony was the glorification of the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia by the Council of Bishops of the ROCOR in New York in 1981. Vladyka wrote an article devoted to the event, in which he wrote: “We must praise the Martyrs with one mouth and one heart… Their prayers are the foundation of our rebirth, their podvig, an example for us, their blood, the justification of the history of the Church in our day.” (15). Another great moment in Vladyka’s life was the celebration of the 1000th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus. He stressed the importance of this event to Metropolitan Vitaly (Oustinov, +2006) in his letter to him after the First Hierarch’s consecration: “Facing you is the task of heading the festive jubilee of the 1000th anniversary of the Baptism of our Homeland. For a thousand years, we live as Christians, which we must show not in word but by deed. We must celebrate this anniversary in such a way that it is a celebration over there, in the Homeland… Our enslaved brethren will hear the voice of the Russian Church from here, they will hear your voice, Vladyko, a hierarch of God.” (16) He organized celebrations in Paris in 1988, about which one participant wrote: “We saw the spiritual, inner depth… the great host of clergymen, and the many worshipers from all corners of the diocese, the great multitude of people, not only Russians, but Orthodox Christians of other nationalities.” (17)

Vladyka headed the organization called Pravoslavnoye delo [“Orthodox Work”], which distributed spiritual literature throughout Russia and disseminated widely information on the persecution of believers in the Soviet Union throughout the West. He also supported the initiative to publish a compendium titled “Hope: Christian Reading.” Harboring a profound love for Russia, Vladyka felt that “Now [in 1974!] we behold a Russia being reborn. Gradually, that which we have awaited for so many years, for which we have worked, for which we have lived, is arriving. Russia is awakening. The better people in the Homeland are speaking out. The Soviet government is at a loss, it dares not deal with its own people, they expel them from the country” (18), including Alexander Solzhenitsyn, whom Vladyka Anthony met in Geneva and always esteemed.

Vladyka was at the same time “universal,” sharing a bond with all Orthodox peoples and all the Europeans who came to Holy Orthodoxy. He loved to serve in the Serbian and Rumanian churches in Paris. Once, a bishop of the Greek Church o Athens prayed at Liturgy in the Geneva Cathedral, and Vladyka not only commemorated him during the Great Entrance according to the custom, but instructed his deacon to serve in Greek. Vladyka was also open to French and Dutch converts to Orthodoxy, and often served in French for their benefit.

Amidst the general difficulties and complications of emigre life, Vladyka was able to preserve peace and love within the diocese Divinely entrusted to him. In the words of his successor, Archbishop Seraphim (Dulgov, +2003), “the clergymen under his omophorion lived confidently, peacefully, wisely and solidly, and so closely-knit!” (19) Vladyka was not only the ruling bishop of the Western European Diocese, but also a regular member of the Synod of Bishops and from 1987 served as First Deputy to the President of the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia.

In the last year of his productive life, Vladyka fell seriously ill. Two weeks before his blessed repose, despite his grave health, he attended the consecration to the episcopacy of Bishop Seraphim, and a few days later, that of Bishop Ambroise, and laid his hands upon both during the ceremonies. Sensing that in this way fulfilled his archpastoral duty, Archbishop Anthony of Geneva and Western Europe ceased to fight his illness and peacefully reposed in the Lord on Septamber 19/October 2, 1993, after Protopriest Pavel Tsvetkoff, at his request, read the Paschal canon in its entirety to him.

The funeral was held at Elevation of the Cross Cathedral in Geneva on October 7, 1993. Archbishop Anthony was buried in the Cathedral itself, at the right-hand wall, where his late brother, Bishop Leonty, is also buried.

Bernard le Caro

(1) After the war, this renowned expert of canon law wrote books and articles directed against the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. Archbishop Anthony averred that these texts were written out of fear of persecution by the communist regime and did not reflect the actual opinion of the author.

(2) Milosevic, D. Milkov manastir ["Milkovo Monastery"]. Smederevo, 1974, p. 50.

(3) NE Novitsky. Otryvki iz moikh vospominanii ["Excerpts from My Memoirs"]. xxl3.ru/kadeti/nikolaev.

(4) VI Kosik. Russkaja Tserkov v Jugoslavii. M., 2000, p. 158.

(5) Ibid., p. 164.

(6) “O poslushanii Tserkvi” ["On Obedience to the Church"]. Vestnik Khrama-Pamjatnika. Brussels, April, 1995.

(7) Metropolit Antonii (Khrapovitskij). Izbrannije trudy, pis’ma, materijaly [Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky). Selected Works, Letters, Materials]. M, 2007, p. 805.

(8) Vestnik Zapadno-Evropejskoj Eparkhii Russkoj Tserkvi za Rubezhom [Messenger of the Western European Diocese of the Russian Church Abroad], No. 39, 1996, p. 20.

(9) Russkoje Vozrozhdenije [Russian Rebirth], ¹ 24, 1983 (Vestnik Germanskoj Eparkhii [Messenger of the German Diocese], No. 5, 1993.)

(10) Lesna Convent publication.

(11) Epistle of the 9th Diocesan Conference of the Western European Diocese, 1969.

(12) Nasha Tserkov’ v sovremennom mire ["Our Church in the Modern World"]. Lecture at the All-Diaspora Council, 1974 (unpublished).

(13) Ibid.

(14) Posev, No. 12, 1979.

(15) Proslavlenije so svjatymi Novomuchenikov I Novykh Ispovednikov Rossijskikh. Doklad na 13-om Eparkhijal’nom Sjezde Zapadno-Evropejskoj Eparkhii ["Glorification Among the Saints of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia. Speech at the 13th Diocesan Conference of the Western European Diocese"], 1981.

(16) Pravoslavnaja Rus’ [Orthodox Russia], No. 2, 1986.

(17) Vestnik Zapadno-Evropejskoj Eparkhii Russkoj Tserkvi za Rubezhom [Messenger of the Western European Diocese of the Russian Church Abroad], No. 32, 1989, p. 8.

(18) Nasha Tserkov’ v sovremennom mire ["Our Church in the Modern World"]. Lecture at the All-Diaspora Council, 1974 (unpublished).

(19) “Kakoje schastje byt’ svjashchennikom!” [“What a Joy to Be a Priest”], Russkiy Pastyr’, No. 36, 2000.

|